IR35: making employment status decisions

Please note: this article does not provide legal advice.

This article is part of a suite - a whirlwind tour to get up to speed on IR35:

- Background to assessment. HMRC's intent, guidance, CEST tool - plus legal cases.

- Making employment status decisions. The big picture on employment status decisions.

- HMRC examples - Alan and Jemima. Quite simple, no CEST.

- Examples - Chenguang and Kaye. Two examples, including using CEST.

- CEST criticisms and responses. CEST can be helpful, despite the criticisms.

- Gaming the system and pressure. HMRC are targeting these.

Background to assessment

In April 2021 the UK’s IR35 legislation will be fully implemented, encompassing all but the smallest hirers of contractors and consultants. Hirer companies will have to decide on the IR35 status of each worker, supplying a status determination statement (SDS).

What determines a person’s status i.e. whether they should be “inside” or “outside” IR35?

Know what’s important

The factors affecting employment status are well known. See these guides:

- 10 factors to be IR35 compliant from www.itcontracting.com

- IR35 employment status from www.contractoruk.com

Knowing these ahead of using CEST will give you confidence in your assessment.

I believe 6 factors are most important in determining employment status. All but one are covered by CEST; commentators point out that CEST misses mutuality of obligation.

| Area | For example |

|---|---|

| Mutuality of obligation | Must the hirer provide and the contractor do work? |

| Part and parcel | Is the contractor integrated into the hirer’s business? |

| Business on own account | Is the contractor truly working as a small business owner? |

| Financial risk | Must unsatisfactory work be remedied at no client cost? |

| Control | Who determines when, where and how work is carried out? |

| Substitution | Can the contractor sub-contract the work? |

I divide these factors into three groups, forming an IR35 “sandwich”.

IR35 heuristics for the many

For the sort of work I typically engage in the IR35 position seems simple.

- The work generally requires a significant level of expertise - actuarial and beyond.

- Given that, not much control is required by the client.

- The "mutuality of obligation" and "part and parcel" points are "no brainers".

- I am clearly in business on my own account.

- CEST says that 1-4 above are good enough to be outside IR35.

- Substitution rights are a nice-to-have addition.

Perhaps similar logic applies to you as a hirer? As someone said to me: "If not, why not?"

The IR35 “sandwich”

The first slice: easily satisfied

Mutuality of obligation should be easy to avoid, unless you expect to have a contract which constantly renews - why would this be in either party’s interests unless they were gaming?

Even with a certain degree of mutual obligation there are other factors at play, which might lead to an “outside IR35” verdict. See the “meat” section below.

Part and parcel is generally easy to avoid. As with other aspects, courts take a less stringent view than HMRC. A court would, for example, understand the consultant having a temporary email address within the hirer’s company e.g. if there were security concerns.

Summary of the first slice

Simple. Almost all employees will tick both boxes and, by default, few contractors will tick either.

The meat

Being in business on one’s own account might be sufficient to justify an “outside IR35” decision. This drove legal victories for Kaye Adams and Lorraine Kelly against HMRC.

Having a variety of clients is one easy way to provide evidence of being in business on one’s own account. Others highlighted by this article include:

- Company stationery - very 20th century for a small business!

- Having a business website - of course!

- Investing in and using your own equipment, not the client’s

There is more: marketing, publishing business-related research etc. Perhaps more materially there is “ebb and flow”. For those genuinely running a business the “own account” test is not hard.

Financial risk can mean a variety of things; having to put right unsatisfactory work at no cost to the client or, less dramatically, just having to fund equipment. Curiously, despite some regarding it as stringent, the funding point seem to be enough for CEST in the case of Chenguang.

Your answers told us that the worker or their business will have to fund costs before you pay them. This suggests the worker is working on a business to business basis.

Source: CEST decision in the case of Chenguang

Summary of the meat

Business on own account is driven by the contractor's business model rather than the work, role or contract, though the contract should reinforce the right to have other clients.

Depending on the length of contracts and age of his business, a contractor should have had multiple contracts, often within a calendar year. This applies to me.

Financial risk includes occasions where work overruns and the contractor needs to finish if not correct the work at his own expense. Regrettably I've also experienced this.

A contractor might carefully share non-confidential points with a potential hirer.

The second slice: occasionally more awkward

Control is perhaps more practical than is sometimes implied. Examples:

- having work start and end times, and even break times in the contract

- having ‘staff’ perks, including provisions for holidays or sickness

- rights of control or supervision over the contractor e.g. by a line manager

The first two would normally be avoided by default. Having a normal place of work might be a requirement, depending on security. A contact will normally have a point of contact to (e.g.) provide project updates and invoices. This is contract and project good practice rather than a boss or supervisory position, particularly where the contractor supplies a high degree of expertise.

Similarly there may be agreement on the scope and methodology. A contractor may well input into or even drive this and it should not be regarded as control.

Substitution can be the most awkward area. Hirers will often value a consultant’s expertise.

Most consultants running a small business don’t aim to outsource their work to others; they enjoy the work and making money! Substitution can arise, due to work pressures or illness. A contract should certainly have a default clause which gives the right to supply a suitably qualified substitute. The consultant should identify relevant substitutes. (Aside: I have three substitutes I have never used.)

Summary of the second slice

This is perhaps the most subtle area, though the "meat" is probably more important. Even with a substitute clause, proving that you "would" use it could be hard - but where does the burden lie?

The control point is more practical and a "confirmation of arrangements" (COA) letter has no legal force, but is a better place than the contract to set out a mutual understanding. COA example.

Examples back up the sandwich logic

Legal examples suggest that the burden of proof on HMRC is high. The BBC presenters, for example, presumably passed the first slice easily, but the meat was critical: they were in business on their own account. On the second slice, substitution was problematic; they were media celebrities of a kind. The BBC exerted a degree of control, but The Upper Tribunal nonetheless said Kaye Adams was:

‘... an expert with a proven track record of presenting popular and successful shows. However, provided that the show continued to answer to the description of “The Kaye Adams Show”, there was no constraint on the BBC’s right to determine the content or format of the show’.

Source: BBC presenter Kaye Adams wins IR35 case

HMRC examples again suggest the role of own account and financial risk are important. Unfortunately perhaps the positions are simpler than they might be. Jemima appeared to do badly and Alan well on all three slices. Too easy!

CEST examples assessed two cases in relation by the HMRC CEST tool. The first was Kaye Adams who won her case. We then take Chenguang, who has some similar features but works in another industry. CEST’s verdict is “outside IR35”. Could Kaye have made her life easier?

A simple process

First and before you assess, understand:

- the work / role. Do you think of it as a role? That could suggest an employed position, especially where the role was previously filled by an employee. Is it a project or a task? In all cases, for a robust decision “think IR35 sandwich”.

- your contractor. We have suggested that the meat of the assessment is the business model of the consultant. Do you understand this?

- the working practices. Will there be genuine supervision or just general agreement on what needs to be done e.g. via a scope of work? Will you accept a qualified substitute?

(1) and (3) feed into sections 1-6 and (2) into section 7 in this example.

Next make the assessment and document your logic.

Check with your contractor. Assuming that you have already identified your contractor, check against his IR35 assessment. If you disagree check our section below.

Finally get the CEST assessment. That should usually agree with yours.

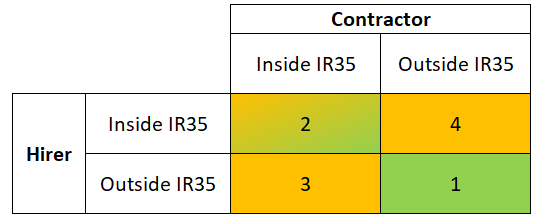

Comparing employment status assessments

When the hirer and contractor disagree

In box 1 both agree that the contract is outside IR35. Naturally it’s not just the contract, but the way the contractor typically works: his business model. This agreement on views is common and you would expect the CEST assessment to agree.

In box 2 both parties agree an inside IR35 status. Perhaps the hirer want to integrate the contractor into its business for a year, with agreed reporting lines. What happens next is down to the parties and depends on the attractiveness of the work and terms. But it probably requires a (temporary?) change in business model if the contractor is to successfully engage.

Box 3’s disagreement is unusual; despite his business model, the contractor assesses the status as “inside IR35”. Perhaps the hirer wants a lot of control or integration. Does the work really require seniority or expertise? If not would it be better done by an employed person? In my view there’s an integrity issue here; the contractor shouldn’t just take the money and let the hirer take the tax risk.

Box 4’s disagreement could arise from the hirer feeling it should “play safe”. Has the hirer understood the contractor’s business model - how would that flow through to CEST’s section 7?

For completeness let’s look at the two situations where contractor and hirer agree.

Where you and your contractor disagree

We might assume the most likely case: the hirer thinks "inside" and the contractor "outside". If this happens your contractor has a right of appeal. But if after discussion - including the nature of the contractor's business model - you still agree it's hard to see what is gained by an appeal.

If acceptable the day rate could be renegotiated, but it might be better to part on good terms.

Two honest parties in this position could usefully compare their CEST inputs and outputs. Do you and the contractor agree on the inputs to:

- the work and working practices in sections 1-6 of CEST?

- the contractor's business model, rights and responsibilities in section 7 of CEST?

When you and CEST disagree

- Confirm that hirer and contractor agree on status.

- If only one of hirer and contractor disagree with CEST check inputs.

- If both hirer and contractor disagree with CEST look elsewhere.

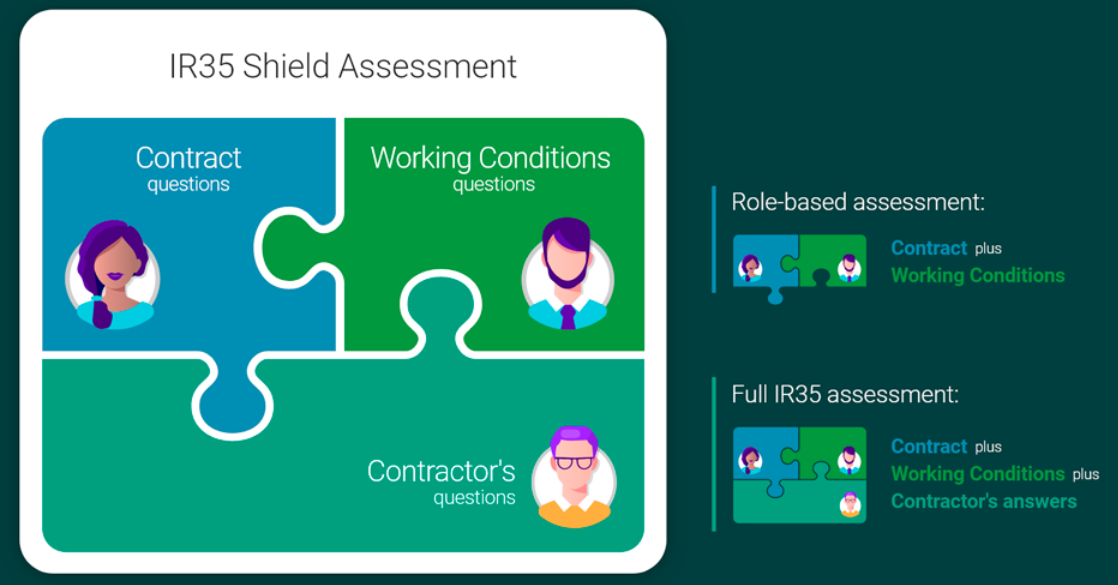

Looking elsewhere: IR35 assessment software

You are not obliged to use CEST and firms have developed alternative assessment tools.

One is IR35 shield which targets agencies, hirers, accountants, law firms and contractors. IR35 shield incorporates inputs from a variety of sources, as suggested above:

Source: IR35 shield

Source: IR35 shield

IR35 shield is not the only offering. Others include:

Looking elsewhere: external advisors

In a particular case taking external advice could be seen as taking reasonable care.

Vendors and advisors have their own agenda. External advice can on occasion be useful. But always? Actuary Guy Thomas offers three advantages of not taking advice (PDF).

- You often save time and money by acquiring expertise and dealing with a problem yourself.

- It increases your autonomy: you become the master of your own destiny.

- It promotes robustness and transparency: when you think for yourself, you understand problems and your own decisions better.

That surely applies when you are to face the same question time and again.

Take care

In summary, take care over:

- deciding everyone is inside IR35 and using a third party to do the PAYE.

- making blanket assessments in general i.e. irrespective of outsourcing.

- outsourcing status determinations - the hirer retains responsibility.

Now let’s look in more detail at what HMRC says.

You can’t just decide everyone is inside IR35 and use an agency to do the PAYE.

A medium-sized company engages an agency to supply workers. The workers supplied by the agency operate through their own PSCs. The client ... elects to simply determine that all workers who provide their services through a PSC will be caught by the new rules, because they undertake similar roles and are engaged under similar terms and conditions. It does this, believing that this will protect it from any liability to pay tax and NICs on payments to those workers. The client passes the same SDS to every worker and the agency.

... as the company has not taken prudent and reasonable steps when making their determinations, liability rests with it. The client has not considered the status of the workers contracting under different terms and conditions, so it has not satisfied the condition to take reasonable care. The responsibility for the deduction of tax and NICs, and the payment of the apprenticeship levy and paying these to HMRC if due rests with the client.

Source: HMRC employment status manual - reasonable care

HMRC warns against blanket assessments in general.

Your client must take reasonable care when making a decision about whether the off-payroll working rules apply.

Applying a decision to a group of off-payroll workers with the same role, working practices and contractual terms may be permissible in some circumstances, but it is not right to rule all engagements to be inside or outside of the rules irrespective of the contractual terms and actual working arrangements.

Source: Important facts for contractors - off-payroll working rules

You can’t outsource status determinations - the hirer retains responsibility.

A large company engages an agency to supply workers ... who operate through their own PSCs. The client decides to subcontract the status determination and production of the SDS to a third party. The client does not introduce any checks or processes to ensure the determinations have been carried out properly ... and does not ensure the third party is suitably qualified to make determinations on employment status for tax.

As the client has taken no steps to ensure determinations have been carried out properly, they have not taken reasonable care. The responsibility for the deduction of tax and NICs ... and paying these to HMRC if due rests with the client.